Food Waste: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

In the last several years, food waste has become an issue of growing interest among activists, scientists, and consumers alike. We are starting to recognize the significance of food waste and the social, economic, and environmental costs associated with it. Understanding and eliminating food waste has increasingly become the aim of scientific study, governments, and nonprofit organizations. This increased discussion may have been instigated in part by a landmark 2009 study, which estimated that America throws away almost 40% of its food. Since then, several reports and studies have sought to uncover this shocking statistic, explore the nature of food waste, and quantify the economic, social, environmental costs of wasted food.

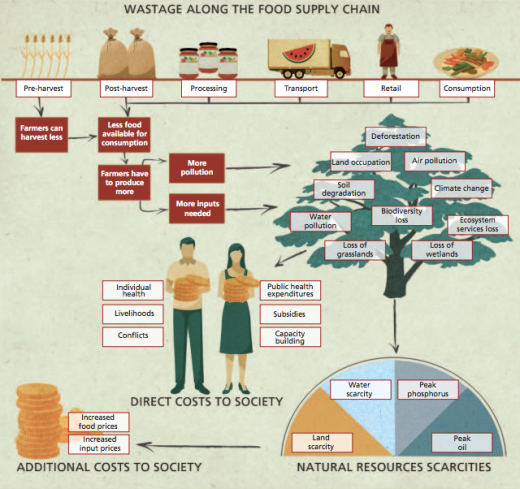

One such study by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that these direct and indirect costs (from impacts such as agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and erosion) added up to $2.6 trillion worldwide and annually. Clearly, this issue deserves widespread attention. Examining these costs of food waste more clearly, we can see that many come from resource loss and other environmental impacts of agriculture. Since much of the world’s resources are used to produce food (40% of its land, 70% of its freshwater, and 30% of its energy), every piece of food that is thrown away represents wasted resources: “huge amounts of unnecessary chemicals, energy, and land” (National Resources Defense Council). In the 2009 study cited above, it was estimated that about 25% of America’s water is used to produce food that is wasted. Activist and author Tristram Stuart points out that the environmental harms of “deforestation, depleted water supplies, massive fossil fuel consumption, and biodiversity loss” are all implicated in the problem of food waste. Additionally, food makes up the majority of waste in landfills, where its decomposition releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas and major contributor to climate change. These environmental costs also lead to direct and indirect social costs in the form of food insecurity, health costs from pollution and pesticide exposure, reduced farmer incomes, lost livelihoods, and increased likelihood for conflict and crime because of all the above factors (FAO).

This flow chart from the FAO study cited earlier depicts some of the social and environmental costs of food waste along the entire food supply chain from production to consumption.

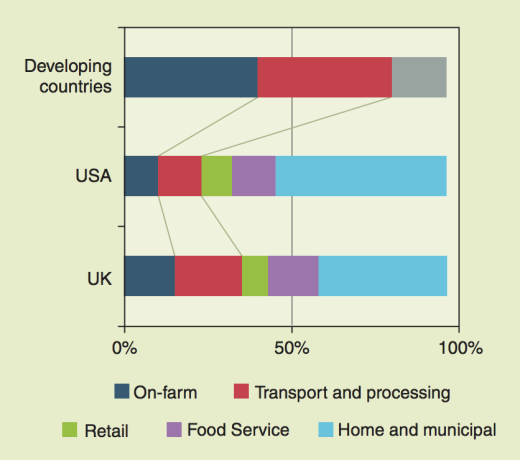

In order to address the root problem of food waste, we must first understand where along the supply chain food is being wasted, which varies widely between developing and developed countries. In wealthy, developed nations like the U.S., food is wasted mostly at the consumption stage. There are several intertwined reasons for this. In highly developed countries, advanced technology in agriculture as well as food processing and distribution means that food is plentiful and cheap. Americans spend less of our income on food than most other countries in the world (6% compared to 43% in Egypt). Therefore, we often do not appreciate the true value of food and buy more than we need without much thought. Additionally, we throw away old food that is still safe to eat, relying on ‘best-by’ labels which “are generally not regulated and do not indicate food safety” according to the NRDC. Though there are other factors at work, low food prices are clearly connected to high food wastage. In an industrialized food system with low food prices, consumers often insist on extremely fresh, aesthetically perfect, and abundant foods. Stores over-stock their shelves accordingly and then end up throwing out unbought foods. USDA standards mean that any produce with a blemish or irregularity does not make it into the food supply so farmers are forced to leave unsightly produce to rot in the field. Fruits and vegetables make up the majority of this on-farm food waste, which is a significant contributor to food waste in developed countries.

In poorer, developing countries, food wastage is more concentrated toward the production side. Lacking technology and infrastructure for transportation and processing means increased losses to pests, spoilage, and weather. Methods to improve shelf life such as pasteurization and refrigeration are almost always absent in places where food is produced mainly by rural smallholders. Unfortunately, there is much less information about food waste in poor nations than in wealthy countries possibly because it is more difficult to gather information about the former. Food waste in developed countries accounts for the majority of worldwide waste, yet in developing countries it is still a huge problem because poorer regions often feel economic costs such as higher food prices and environmental costs such as water depletion more severely than developed areas do.

The above chart from a 2010 report on food security compares the sources of food waste in developing countries to those in developed countries such as the U.S. and the U.K. Each bar represents the total food waste in a given country, which is divided by color into different categories of food waste. For example food wasted during the “transport and processing” step of the food supply chain is shown in red. The chart shows very clearly that food waste which occurs “on-farm” and during “transport and processing” is the largest contributor in developing countries, whereas in developed countries “home and municipal” food waste dominates.

In an attempt to mitigate these costs which food waste incurs on developing countries, governmental and non-governmental organizations bring improved technology and methodology in food production, storage, transport, and marketing. For example, a recent article in National Geographic explained that “after the FAO gave 18,000 small metal silos to farmers in Afghanistan, loss of cereal grains and grain legumes dropped from 15 to 20 percent to less than 2 percent.” This advancement no doubt improved local livelihoods and contributed to a more secure, steady food supply.

NGOs have also helped to reduce food waste in developed countries like the U.S. These efforts have taken many forms, for example charities that glean unharvested food from farm fields or redistribute unsold food from grocery stores to food shelters. One innovative company called Leanpath produces technology to help retailers monitor their waste, which causes stores to realize the financial cost of wasting food and subsequently leads to decreases in food waste. In the U.K., a huge campaign by the Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) has increased public awareness so that food waste is now a major topic of discussion and thought.

This fall, activist Rob Greenfield rode across the country on his bike and ate only food he found in dumpsters, along the way hosting “Food Waste Fiascos” in which volunteers rescued food from grocery store dumpsters and then gave it away to anyone who needed it. The above photo is from one such gathering in Madison, Wisconsin and shows only a small fraction of the food salvaged from dumpsters there.

Increased public awareness can help begin to shift strongly ingrained habits and mindsets surrounding the value and consumption of food. Even though a simple public awareness campaign might seem like an overused and unhelpful tactic, I think in this case it is a valid approach when implemented in strategic combination with others. Consumers are the greatest contributors to the food waste problem in developed countries, so we are necessarily a huge part of its solution. Simply appreciating all the work and energy that goes into food helps to value it and pay more attention to purchases and habits.

Still, top-down approaches in policy and regulation can also be extremely effective in combating food waste. In 2012 for example, Belgium passed a law requiring supermarkets to donate unsold products to local charities, using these companies’ surpluses to help meet the food needs of the poor. Rob Greenfield points out the many benefits of grocery stores donating food waste: “stores that donate… get tax write offs which means it’s profitable to donate, they spend less on dumpster fees, and most importantly they are doing what is right for their community.” Relaxing laws about cosmetic food standards can reduce on-farm waste of ugly but perfectly edible produce. Tristram Stuart’s idea to remove the ban on feeding food waste to pigs in the European Union would help to cycle the wastes of our food system right back into food production.

Combating food waste is an essential part of meeting the food demands of a growing population: just a 15% reduction in food waste in the U.S. could feed 25 million Americans, according to the same 2009 study cited earlier. Though many stress agricultural intensification and yield increases as the only solution to problems of food security, reducing food waste is clearly also part of the answer. When the problem is that many people don’t have enough food, we can try to grow more food and achieve yield increases of a few percent per year or we can distribute more effectively the nearly 40% of food that is currently being thrown away. It is extremely encouraging that this second option is already being explored and that so many viable solutions to this huge problem have been proposed and implemented. Through a diverse range of policy measures, cultural shifts, and non-profit efforts, we are slowly reducing food waste and its costs to developing and developed countries alike.

Trackbacks