Farm Together, Now?: A Fifteen Year Reflection

Farm Together, Now?: A Fifteen Year Reflection

By Daniel Tucker

“Every minute I speak to someone like you, that’s that many minutes I’m not perfecting my life philosophy.” That’s the greeting I got when I traveled nearly 700 miles to visit and interview a farmer back in 2009 for the book “Farm Together Now: A portrait of people, places and ideas for a new food movement” (Chronicle Books, 2010). Whew, I thought – I appreciate the clarity of purpose but as a greeting it was rough.

We went on to spend the day together and I started to see more about this tension. He really just wanted to work on his plants and refine his methods, but there was a tremendous pressure to represent himself to others. That was particularly prevalent at the time – just as food was getting fancy and organizations were cropping up to educate people about how the food systems could be more just and sustainable. Many food activists prefigured the lifestyle influencer route, spending more and more time doing the representing of the work that took them away from “the work” itself.

In working on the book a related phenomenon that became apparent was the way that many urban gardens were encouraged to overstate their effect, often using the admirable frameworks of food sovereignty and justice, to describe projects that materially had little impact on the local food system, while having all sorts of other impacts that went unmentioned. This was likely a practical solution to funders that encouraged such transformational rhetoric, but in many ways obscured the fact that what most urban gardens do is get a small number of people outside and spending time learning and exchanging with neighbors and building skills and confidence. But they were not changing complex and hardened aspects of food chain distribution networks. The unfortunate trade off was that it was harder to understand what those projects really did accomplish – which was a lot, but just not what they said in their mission statements, grant applications and social media posts!

And so Farm Together Now came out and we did a national book and press tour and did our own representing. And I kept thinking about that awkward greeting and what lessons it held, for me personally, for the food movement and also for people trying to enact change more broadly.

What I started to realize for myself, was that this tension between the doing and talking or representing and the pressure to overstate the impact of one’s work, this was a problem that had some unique similarities (and potential solutions) in my field of origin which was art. And so while I was eager when I was co-creating Farm Together Now with my collaborators to step out of art and engage in food (a field I thought was more fundamental to life), it started to pull me back in. I realized that through the lens of this tension that art and farming surprisingly shared some problems, and that when such correlations present themselves it’s worthwhile to think about how they can be brought in dialogue.

My next book, Immersive Life Practices, set out to explore this question. It was released 10 years ago (SAIC/University of Chicago, 2014) and looked at art projects that tried to blur the line between the doing and the representing. This re-investment in art also had a marked influence on how I engaged with food systems for the following decade – developing curatorial projects featuring art about the logistics and distribution of food, as well as ecology and bioregionalism more broadly.

In retrospect, there is a strong relationship between art and farming. I’ll attempt to outline a few here:

- The kind of food and art we get when utilizing market-based value systems is predictable and boring.

- Growing food, making art, sharing food and experiencing art – these activities do a lot for our well being that are difficult to articulate. The framework of intangible cultural heritage could apply to both, if it was expanded to include more contemporary practices in each field.

- There are forms of both art and food that are more introspective and draw on an individual’s hard work and exploration of the capacity of self, and there are forms of both art and food that are all about systems and social dynamics. It is hard for both fields to account for that wide spectrum of practices and forms, but the bigger the tent – the better.

- Art and food culture both suffer from a kind of alienating self awareness/referentiality – did you go to this restaurant or this museum and follow the dots between this chef or this curator. But sometimes we just encounter art or a meal and want to appreciate it through other lenses. These can be aesthetic experiences embedded in everyday life that connect us to places and one another, make beauty accessible and reclaimed from the market logic and disciplinary boundaries that encourage these alienating ways of communicating. We all deserve transformative experiences with food and art and nourish us!

- Because food related organizations and art related organizations often end up prioritizing education, they have an opportunity to contribute more to conversations about informal, collaborative, self-directed and process-based learning. A barrier is that they don’t often express this as their primary goal, because their fundraising priorities pull them in so many directions (to the farmers, say you’re transforming the food system; to the arts administrators – say you’re changing the world through art). This pressure to overstate impact can distract from a more precise grappling with what the work is and what it achieves.

- And finally, one of the things that I appreciated the most about talking to farmers across the country was that clarity of purpose I mentioned earlier, which is the kind of thing that leads people to say something like “Every minute I speak to someone like you, that’s that many minutes I’m not perfecting my life philosophy.” This binds farmers to artists, who are very conflicted between making/doing and showing/talking. Not only is this a potential bond to connect their outputs, but it also offers an expanded peer group to help them think through how they want to do their work and structure their lives.

As I think back about crisscrossing the country with my collaborators Amy Franceschini and Anne Hamersky interviewing and photographing activist farmers from the red clay under the urban skyline of Atlanta to the drought resistant seeds of the desert Southwest – I feel immense gratitude for who we met and what they shared with us. In some cases it was an afternoon interview and a tour, and in others it was a meal and overnight camping on their land. Some we visited only once, others we continue to stay in touch to this day. In every case they offered some access to their collaborators, staff and community members to help us get a sense of the larger world around their farm. And in our conversations they brought us into their pre-histories, their proud current achievements, their challenges and their hopes for the future.

If we were to do a sequel book, we’d have some new questions and as some of the farms have closed – we’d probably look at some new farms while revisiting some from the first book. The accessibility of robotics, the altered public policy landscape, the growth of distribution hubs to support regional economies, the focus on equity in land ownership, dramatic changes to growing climate and weather – are just a few of the new lines of thinking and work that farmers today have been grappling with that I imagine we would delve into. For now, I cherish the lessons learned and hold out hope for more art and food collaborations. They truly are the nourishment I live for.

Note: All Photos courtesy of Anne Hamersky for Farm Together Now (Chronicle Books, 2010)

2020 Update: Joe Hollis of Mountain Gardens

Mountain Gardens in 2009, Photo by Anne Hamersky for Farm Together Now

We are pleased to share this update from Joe Hollis of Mountain Gardens:

“Mountain Gardens carries on along the course indicated in the book. The gardens have expanded, the plant collection enlarged, we now have a considerable you-tube channel of plant and garden videos, I recently resigned from teaching herbal preparations and medical botany at Daoist Traditions with the intention of starting a herb / permaculture school here (see video on my website www.mountaingardensherbs.com). I am 78 and, since a car wreck a few years ago, not as speedy. My efforts to develop a small, consensus-based community to carry on my work have been frustrated (managed to accumulate a core group of three, and they started a feud with each other – is there an emoji for throwing up your hands in despair?).

In response to Covid, we are primarily interested in serving our local community (South Toe Valley). We are offering a range of immune boosting and anti-viral tinctures and plants based on the latest research from China & US. (sorry, we do not ship tinctures) Emerging viral and bacterial diseases will be the story going forward and pharmaceuticals will not work (viruses quickly develop resistance) – herbs are our main (I think only, but maybe I’m missing something?) hope. Therefore Mountain Gardens finds itself on the frontline but, to reiterate, we are only trying to save our valley (and be an example of how others might save their valley). I think Mtn Gdns includes the largest collection of medicinal herbs in E. N. America but not sure for how long – the rising line of the complexity of the project has long since crossed the declining line of my ability to keep track of it.

Here is a video of Mountain Gardens prepared this spring for the Medicines from the Earth (herbal) Symposium, which was online this year:

See the full blogpost with plant names here: https://www.mountaingardensherbs.com/blog/2020/6/11/a-plant-wal

Fifty years ago I thought I was creating an example of how people could live on earth without screwing it up, causing war or making themselves unhealthy; now I realize that actually I have been building an ark.”

As part of our 2020 updates about Farm Together Now featured farmers, we are sharing these updates from Devon G. Peña of The Acequia Institute in San Luis Colorado. We would also like to dedicate this post to Joe C. Gallegos who passed away in December of 2016. Gallegos was interviewed in Farm Together Now with Pena and was a pillar in the community.

2020 Updates from The Acequia Institute:

“Our work at The Acequia Institute (TAI) is blossoming and there is so much going on I can only highlight a few things here:

- TAI is now a “grow-out operator” for a Seed Rematriation Project to preserve and return bioregional landrace varieties of corn, bean squash, peas, and orach unique to the Upper Rio Grande communities of San Luis and Ortiz, CO, Taos Pueblo, Vadito, and other New Mex. locales. We have about 3 acres at three different sites (to separate the maize varieties) and these will be returned as seedstock to replenish acequia farmers in these communities of origin and diversification.

- TAI is also hosting a high altitude hemp production experiment. This involves “Red Kross” a native landrace heirloom that has been grown by Native American tribes for decades and is used as traditional medicine. Red Kross is a 80-100 day auto-flower variety and is drought resistant and apparently adapted to high elevation and extreme hardiness. That is the experiment: How will it do at our new field in San Francisco, CO at 8100′? The project is made possible by our allies, Lightning Horse and Bill Nesbitt of Pacific Northwest Indigenous Farmers, LLC in Oregon.

- We now have an Executive Director, Buffy Turner (Cherokee) who is leading two major projects: (1) The convening of a council of advisors to begin planning the transformation of TAI from a simple 501(c)(3) into an inter-tribal land trust. We are rematriating the 181 acres of land along with water rights and the conservation easement at the TAI almunyah to a four nation council consisting of members from all the Indigenous peoples with attachments and heritage claims to the San Luis Valley. These include Caputa Ute, Dine (Navajo), Tewa (Taos Pueblo), and Xicanx/Genizaro (varied Mexican-origin) peoples. Two-spirit people are playing a major role in this council. (2) The launching of a capital campaign to construct a series of adobe buildings to house Institute headquarters, seed sanctuary, classrooms, and dorms centered around a traditional ceremonial placita (communal square).

- Representing TAI as part of a UN certified delegation sponsored by the Asociacion Andes, I was a co-author and facilitator of the Ek Balam Declaration, a manifesto to protect the sacred in corn, and which was presented to the 13th COP of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in Cancun, Mexico (Dec. 2016). This grew out of the earlier work of the Voces de Maiz/Voices of Maize network which included collaboration with the “Braiding the Sacred” group, another network of Indigenous corn protectors. The Ek Balam Declaration was followed with an invitation to submit a Strategy Brief to the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues which we did in April 2017.”

Here are some photos to accompany update, from the final stage planting of the Rematriation Milpa #1 at Rancho Chiquito (San Francisco, CO). Native land race hemp variety known as “Red Kross” used in traditional medicine across Turtle Island. In partnership with the Northwest Naive American Farmers, LLC (Oregon).

2020 Updates! 10 Years Later!

Starting next week we will share some updates from farmers who were featured in Farm Together Now back in 2010. For now, feel free to read some of the interviews from the book here:

Starting next week we will share some updates from farmers who were featured in Farm Together Now back in 2010. For now, feel free to read some of the interviews from the book here:

Angelic Organics Learning Center, Aquaranch, God’s Gang, Hunger Coalition, Jim Knopik, Joe Gallegos & Devon Pena, Joel Greeno, Mountain Gardens, On-the-Fly Farm, Sandhill Farm

Interview with Mark Kimball of Essex Farm (Part Two of Two)

This post is a continuation of the first part of my interview with Mark Kimball of Essex Farm, which you can check out here if you haven’t had a chance yet. In the first part of the interview, I talked with Mark about the philosophy and practices he employs on his farm in Essex, New York. You can also find a short introduction to the incredible Essex Farm in that post. Here, you will find more about Mark’s philosophy on farming, as well as some fascinating thoughts surrounding the issue of labor on the farm.

This post is a continuation of the first part of my interview with Mark Kimball of Essex Farm, which you can check out here if you haven’t had a chance yet. In the first part of the interview, I talked with Mark about the philosophy and practices he employs on his farm in Essex, New York. You can also find a short introduction to the incredible Essex Farm in that post. Here, you will find more about Mark’s philosophy on farming, as well as some fascinating thoughts surrounding the issue of labor on the farm.

* * *

Simon Willig: How has your philosophy and thinking about farming changed over time, as you have done more farming or done more faming in this specific place?

Mark Kimball: I think that my life has been a series of both deeper philosophical questions––deeper than let’s say, “what am I having for breakfast?”––and then practices. I think for me philosophically it has only been through time and farming that I have distilled the idea that agriculture can be more broadly defined than it is usually, and that it’s basically the foundation for culture, and that we can look at agriculture and industry united on landscapes to meet human needs.

I think when I started out I wanted to see, on my practical goal set, it was: can I make a living growing vegetables? I think now the shift is: can I, with a team of people, meet our human needs with a given landscape or landscapes and do more good than harm? I think there are echoes of that in my early thinking and writing, but I don’t think I really touched and tasted that until I learned how to build barns and homes and learned how much gas I go through every year using car to visit family and relatives or taking a plane somewhere.

I think what’s changed philosophically is that as I get more skilled in the physical world, I understand cause and effect a little bit more. So while it’s incredibly convenient to have UPS drop off our next day supplies to the farm or go to the hardware store, I also understand a little bit more of the global infrastructure necessary to do that. And I think every time you do something in the physical world you get more connected to those pathways just by understanding that, for example, to move a ton of something across the farmyard takes as much tractor or horsepower as you’re talking about what it took to move a ton of seed from another farm to here, or what it took to move a ton of food to Plattsburg from Killy [two nearby towns].

So I think flip Middlebury’s no vo/tech [vocational/technical training] here policy on its head and I would say, “Let’s not just limit ourselves to who can make a weld waterproof” but look more at what tools welding is conferring on our bigger relationship to society and the environment. And so for me there is a great excitement in trying to bring to higher education an integration of visceral, physical world experience and highfalutin philosophical and scientific thought, because I think that without one the other becomes less feasible. Without understanding metallurgy, it’s not as fun to join two pieces of metal, but you can still just do it. You can just learn “Here’s how you strike the welder, here’s how you make this weld, go home” but it’s also really fun to think about how the metal influx is lining up, etc. That’s a little tangent to where you were going, but I think that I really have come to see that if I were in charge, if I could play god with higher education, it would start out with very physically grounded questions of what makes things work.

SW: So I think I’m hearing that over time you have had your physical, on-the-ground experiences contribute to your larger philosophies. Do you feel that it’s also gone the other way and that over time your larger philosophies have contributed more to your on-the-ground experiences and practices?

MK: As a short answer, I think that contextualizing your physical world activities and tying them to goals and philosophy brings more meaning to them. So in other words when I milk a cow, knowing a little teeny bit about cow digestion and pasture management, thinking of it in relationship to dairy product, and the whole raw milk debate, adds some sort of sub-conscious or conscious benefits of milking. And I think connecting consumers to their product and the philosophy of the farm makes it so that when I’m milking cows I’m not just creating a commodity that disappears, I’m creating something that within a day or two is going into people’s mouths and that’s connected to the process of digestion and human effort and food.

So yes, I think it does go both ways in that some of the deeper goals of the farm end up really giving you a reason to take a deep breath while you’re milking the cow and not feel like a vo/tech welder who is just going to try to make a pay check for the rest of your life, but instead say “Oh, this was in line with our bigger goals because it does this and this and here’s where it’s not in line.” So yeah I think it does work both ways for me, but because I don’t get to do as much of the routine work on the farm I think it becomes all the more poignant and fulfilling to be able to do that stuff.

SW: Going back to what you were saying earlier about trying to do more work with horses, who performs the work on your farm (animals, humans, tractors, etc.) and how do you approach and look at that?

MK: It’s a question to which we’ve failed to create the answer we looked for in the beginning. Our goal was to find a group of people who would work along side us over time and get better at this practice here on this piece of land with these goals. And what we’ve become more known for is that we’ve trained dozens of young people and given them experience to go off and start their own operation.

But on a more sort of “how do we do it?” level, we use horses, tractors, underpaid labor, paid labor, volunteers, visitors, by any means necessary to get the job done. I think when we first started the farm, more farmers spent more time on horses, which left a lot of the work to these other farmers using fuel [to grow the feed and bedding for our horses]. So at first, we sub-contracted a lot more purchase of hay, grain, and bedding then we do now, and now we’re doing most of that in house so we are using a lot more fuel as a business but before we were hiring other people to use fuel.

And we hired migrant labor this year for two weeks to help us with fall harvest. But I think the other way we get it done is that we spend a lot of time asking people to help us, so we call people up and say “Hey, can you help with this? Are you willing to do this?” Recruitment and enlistment are essential, whether it’s the Middlebury team that comes over and knocks it out of the park with squash sorting and clean up or summer kids who come for a summer and basically destroy their bodies and laugh while they’re doing it. It’s a mixed crew, but what are missing mostly, what we look at building next year, are skilled farmers.

It’s much easier to find post-production people than it is to find skilled farmers, so we’re consistently finding people who can solve the recipe for making sausage and do that well. It’s maybe not so much that they’re a professional butcher, but these kind of “front of the house” people are easy to find. I think it’s much more challenging to enlist people who really understand how to farm. For example, we had two pigs farrow [give birth to a litter of piglets] this fall and somehow our animal team, which has done farrowing before, didn’t provide them with enough shelter so we lost two batches of piglets to mismanagement and lack of communication. And Kristen and I look at each other and we raise eyebrows every time it happens. And we just say, “What part of this didn’t we go over? Why didn’t we know that this was close? Where did we mess up? And that’s always a challenge.

SW: How do you approach pest and disease management?

MK: I think we balance the idea of animal-positive and plant-positive solutions with more direct pest control. In other words, improve animals’ feed quality, improve their fertility and if something becomes a major economic or health concern then start looking at disease control and pathogen control. I come about it with a philosophy of “Just grow more, let’s grow it better each year, yeah we’re going to have losses, go forward.” So I think we’re walking pretty nicely through a balance of: on the big picture let’s create healthy systems, and on the small picture, when we screw things up, let’s look at short-term solutions for killing rats, and improving our farrowing rate, for example. Kristen and I are now talking about for next year, “How do we do better pig farrowing? If we have beginners doing it, what are the systems we need in place to really get people better at that and how do we do that?”

SW: You’re always talking about trying to get people on the farm and getting people excited about farming. Additionally, farming and getting back to the land are becoming increasingly attractive to young people. In light of these things, can you share some thoughts on this increased interest, the perspective these young people bring to your farm, as well as the possibility of people romanticizing or idealizing the farm life?

MK: It’s a perennially challenging workplace as an employer and an employee. There are people out there, typically migrant workers, who are used to repetitive agricultural tasks like milking, harvesting, and sitting in tractors. Then there’s a group of other people who are looking at it more from a philosophical, environmental angle and don’t have skills and don’t have the patience to just do the same things their whole life. And being able to juxtapose both of those at the farm is always great because it sort of leads to excitement.

And I think that the key is, if you have an inclination toward agriculture, follow it at all costs, but realize that as of yet, there’s not a road to you’re physical or fiscal security. You’re in a high-risk physical job; your body could get hurt; you’re doing a lot of work. And fiscally there’s no bottom line yet to farming. It tends to lose money wherever it’s practiced. Our government has created ways to keep farms alive, but just barely. So when you go into it you have to be aware that both your body and your bottom line can fail.

I fully support people that are walking down the farm road. And I think that you owe it to yourself as somebody in a country where we are, entirely subsidized by larger socioeconomic and environmental choices to go bravely into it. In other words, don’t listen to other people and if your gut sense is to go into farming, go into it. So I highly recommend it, with the cautionary tales that are concomitant with farming: be careful, make sure you have people that can help you out if you make economically or otherwise stupid decisions. Make sure you’ve got some people around you to help you get out of those consequences.

* * *

I hope you enjoyed reading about Essex Farm and all the ideas and practices behind it. You can learn some more about Essex at their website and their Facebook page. Thanks for reading!

Simon

Interview with Mark Kimball of Essex Farm (Part One of Two)

Last month, I had the opportunity to talk to Mark Kimball of Essex Farm and ask him about his practices and philosophies. Mark, his wife Kristen, and a shifting crew of farmers and workers together run Essex Farm on 850 acres in Essex New York. They produce about 50 different types of vegetables, several different types of grain depending on the year, hay, meat, dairy, and eggs.

Last month, I had the opportunity to talk to Mark Kimball of Essex Farm and ask him about his practices and philosophies. Mark, his wife Kristen, and a shifting crew of farmers and workers together run Essex Farm on 850 acres in Essex New York. They produce about 50 different types of vegetables, several different types of grain depending on the year, hay, meat, dairy, and eggs.

One of the things that makes Essex Farm unique and well known is their full diet CSA sales model, a twist on the typical CSA (Community Supported Agriculture). In a CSA, consumers purchase a share at the beginning of the growing season and receive a weekly mixed basket of whatever is growing on the farm at that moment, rather than buying individual products. In Essex’s full diet, all-you-can-eat CSA, families pay for membership on a per-person basis, and then visit the farm every Friday to pick up whatever food they might need for the following week, and however much they need. Customers therefore get nearly all of their dietary needs met at one place. The share includes different meats, dairy, flour, herbs, a huge variety of veggies, and maple syrup.

I have visited Essex Farm a few times and have really enjoyed being there, talking with Mark, and learning about their operation. I wanted to interview Mark to hear more about his philosophy and thought behind the farm.

With this basic introduction to Essex covered, I will provide my interview with Mark, below. Because of the length of the interview, parts have been removed or edited. However, I have maintained the meaning and integrity of Mark’s ideas. Also, it helps to know that I attend Middlebury College, which is why Mark brings Middlebury up in a few instances.

* * *

Simon Willig: Can you talk a little bit about the reasoning behind your full-diet CSA?

Mark Kimball: It just seems to me that it meets a lot of my needs as a consumer to have a full diet from one place. And then the model also makes sense for a producer to have, given that waste streams from grain production become bedding for animals. Integrating these processes on both sides seems like a pretty good direction to head.

SW: What is at the core of your philosophy on farming? How do your broader philosophies about things such as the environment play into this?

MK: I think the first thing is: can I live in a way that does more good than harm? I want to derive my life philosophy from that. I think that’s still an open question, and I think there are some sort of obvious answers and some answers that I think are hard to pin down. As it translates into farming, I see farming fairly broadly defined as the production that goes into meeting human needs and inherently using the land as the substrate for that. So, then, farming is combining sunlight, soil, geothermal, wind, and whatever it takes to meet human needs in the most creative way. And to me that involves going way beyond food production, although here we haven’t done much of that besides firewood for the members and for ourselves. And I guess we’ve also met human needs in terms of a place where people can socially commit to each other and to a landscape.

I think the first step for me in redefining how I want to measure my success as a farmer or failure (and I think it’s probably likely to have failure before success) is: can I set up a way to see how much sunlight I can capture, maybe even through wind and photovoltaics, but primarily through plants, to meet those human needs in a long- and short-term strategy? So one of the equations I say (in sort of faux chemistry geekdom) is: who can catch the most photosynthate, keep it where you caught it, and still provide the most benefits for society?

So those are all very high in the sky ideas and I think the reality is we are much more constrained by fiscal and social constraints than we are by environmental ones at this point because we’re not having to pay the cost of our negative environmental impacts. I have a much harder time figuring out how to pay my bills and train my labor force, so I don’t really have time to address some of those more fundamental questions. Just on a financial or employer/employee relationship, I’ve got a lifetime of work ahead of me. So it’s interesting to have all three metrics (the fiscal, personnel, and environmental) running around inside.

And I think the challenge for me as a leader here is: can I make meaningful steps (that can get assessed, revisited and improved upon) toward these broader goals as a farm? So the other philosophy I’m working towards is how do you make day-to-day decisions given these lofty goals. And I think that’s another fun part of the human condition that I get to play with here.

SW: How does your philosophy on something like climate change fit into your philosophy on farming?

MK: That’s a good question because I think everybody is now in the kind of progressive environmentalist camp. Everyone is thinking and talking about ways to do that. So I guess there’s sort of a two-part answer.

One is at a very economic level: what are the best, most economically viable practices agriculturally to regenerate soil, air, and water? While air is the most directly tied to climate change, obviously water and soil are still hugely important. So if we’re going to sequester x tons of carbon in the soil, what does that do and who feels it? I think there are the broad economic questions that I have seen very few satisfying answers to. For example, you shared earlier that grass-fed cows might produce more methane. So how would we adjust that production if that is true? And do we go down that road and look at that? So I think there are tons of granular details that I need to understand to make wise production decisions.

And then I think there’s another side, as a way to meet a short-term sort of hopeful goal. And that is: is what we’re doing socially in this community with our members, and in New York City with our New York City members a constructive step towards mitigating climate change? In that by enlisting members to cook whole foods we’re changing their buying patterns to support what they ingest, at a sort of crass way to say it. But by that they’re actually changing where their atoms come from, and becoming more connected to the fact that the atoms they ingest are land-based in a way that every food is, but this way at least they’re conscious of it.

So is there a way to address climate change by increasing individual consciousness to the food we eat? I think that’s a question not a statement. It may be that we’re just convincing ourselves that small, diversified farms are somehow more sustainable and by eating that food we’re becoming better more responsible human beings. And those could all be false assumptions, but I think on some level that may be the most that we’re doing right now. That is: children and families, now some of them have gotten 50% of all of their food-borne atoms coming from this little piece of dirt, and the farmers here that are tending it.

So maybe we look at that one of the ways that people can get reconnected to some of these questions at least and sort of pass the questions forward to the next generation and we say “Okay, we created a template, a palette, a springboard for you to make way better decisions than we’re able to make because we don’t have the time, information, or societal commitment to these goals yet.”

But I think individual health is, if nothing else, good for itself and I think individual health might be a microcosm of creating planetary health. So looking at your own body as an organism maximizing its health, I think is a nice starting place for looking at the health of the biosphere.

SW: You touched on this a bit, but within this philosophy what are the goals that you are constantly striving for?

MK: I think that is a separate question in some ways and if we get down to how to you take philosophy and wake up and live it, having looked at the last five years of production here, where I’m heading in the next short-term is: let’s start measuring things that are easy to measure. It may be the kind of thing where I talk to people at Middlebury and say, “Hey can we get some undergrads and grads to help us measure simple things? If you’re here for a year do you want to measure all of our fossil fuel inputs?” And that depends on how much diesel, how much grease, how much motor oil, how much electricity, how much whatever. So starting to measure whatever baseline inputs that we’re bringing on to the farm seems like a good starting place for a goal agriculturally for me.

And I think more than that, a good thing to measure is how many horse hours we put into the farm, and for the short-term coming up with a way to measure how many hours we hitched this year and how much we did during those hitches. Maybe then the second part of that is: how much would that have taken with tractors? And maybe even going further, deriving some of the pros and cons of the two different systems we have going on at the farm here. So I think the short-term goals would be: can we increase our solar (which we have here) and horse-based production per gross dollar of income? And we can create a fraction and figure out horse hours per dollar and go forward and say “Okay, we did 0.2 horse hours per dollar this year and we’re aiming for 0.25 next year.”

The other short-term goal is––looking at Wal-Mart as maybe the most successful one-stop shopping to meet human needs in the light of consumer demand thereof––how many of those goods can we create in a regional way that allow consumers the same sense of “Wow I just got all my stuff and it was cheap and it met my needs”? How do we add a higher value than what Wal-Mart does? That could involve asking: should we or could we get high-efficiency European [wood] stoves imported into this region so that we can burn firewood cleanly? Looking again at the needs of food, shelter, water, entertainment, which is the lowest-hanging fruit, both for the farm and as a bunch of consumers? And we should have the goal be to ask that question honestly and say “Alright, what are we good at? What can we provide reasonably? Who’s going to do it? And then what’s our short-term goal for that?”

So I think that’s the bigger question in agriculture: can agriculture move beyond the food movement to look at fiber and fuel needs and shelter needs? And what are reasonable ways to do that in a really economically efficient, global market place? How do we deal with economic inefficiency if it’s more environmentally efficient? So that wanders a little bit from your question, but I think it’s important to be aware that within that goal of doing more good than harm, there may be alternatives to just growing carrots.

So maybe we say, “If you’d like a firewood share, you have to buy one of these high-efficiency stoves and if you do that then firewood will be included in your share price.” So then there’s sort of a buy-in. But trying to figure out specific examples that work on all levels would be great. And I’m not saying it’s firewood and stoves. It could be drive-in movies and then we have local entertainment instead of people having to drive to Plattsburgh. That’s a ridiculous example maybe, but looking broadly at what humans are consuming and figuring out which of those things could be tied to a piece of land is a really exciting proposition that usually leads to more complexity and intrigue, which I think may be part of the solution to the bigger human problems.

* * *

Due to the length of the interview, I have split it into two more manageable posts. The second part will include more about Mark’s philosophy and practices as well as the fascinating topic of labor and what powers Essex farm. You can now find the second part here. Thanks for reading and stay tuned for the second part, which will come in about a week.

Simon

Food Waste: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

In the last several years, food waste has become an issue of growing interest among activists, scientists, and consumers alike. We are starting to recognize the significance of food waste and the social, economic, and environmental costs associated with it. Understanding and eliminating food waste has increasingly become the aim of scientific study, governments, and nonprofit organizations. This increased discussion may have been instigated in part by a landmark 2009 study, which estimated that America throws away almost 40% of its food. Since then, several reports and studies have sought to uncover this shocking statistic, explore the nature of food waste, and quantify the economic, social, environmental costs of wasted food.

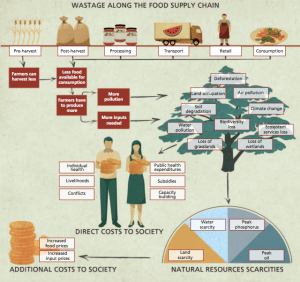

One such study by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that these direct and indirect costs (from impacts such as agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and erosion) added up to $2.6 trillion worldwide and annually. Clearly, this issue deserves widespread attention. Examining these costs of food waste more clearly, we can see that many come from resource loss and other environmental impacts of agriculture. Since much of the world’s resources are used to produce food (40% of its land, 70% of its freshwater, and 30% of its energy), every piece of food that is thrown away represents wasted resources: “huge amounts of unnecessary chemicals, energy, and land” (National Resources Defense Council). In the 2009 study cited above, it was estimated that about 25% of America’s water is used to produce food that is wasted. Activist and author Tristram Stuart points out that the environmental harms of “deforestation, depleted water supplies, massive fossil fuel consumption, and biodiversity loss” are all implicated in the problem of food waste. Additionally, food makes up the majority of waste in landfills, where its decomposition releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas and major contributor to climate change. These environmental costs also lead to direct and indirect social costs in the form of food insecurity, health costs from pollution and pesticide exposure, reduced farmer incomes, lost livelihoods, and increased likelihood for conflict and crime because of all the above factors (FAO).

This flow chart from the FAO study cited earlier depicts some of the social and environmental costs of food waste along the entire food supply chain from production to consumption.

In order to address the root problem of food waste, we must first understand where along the supply chain food is being wasted, which varies widely between developing and developed countries. In wealthy, developed nations like the U.S., food is wasted mostly at the consumption stage. There are several intertwined reasons for this. In highly developed countries, advanced technology in agriculture as well as food processing and distribution means that food is plentiful and cheap. Americans spend less of our income on food than most other countries in the world (6% compared to 43% in Egypt). Therefore, we often do not appreciate the true value of food and buy more than we need without much thought. Additionally, we throw away old food that is still safe to eat, relying on ‘best-by’ labels which “are generally not regulated and do not indicate food safety” according to the NRDC. Though there are other factors at work, low food prices are clearly connected to high food wastage. In an industrialized food system with low food prices, consumers often insist on extremely fresh, aesthetically perfect, and abundant foods. Stores over-stock their shelves accordingly and then end up throwing out unbought foods. USDA standards mean that any produce with a blemish or irregularity does not make it into the food supply so farmers are forced to leave unsightly produce to rot in the field. Fruits and vegetables make up the majority of this on-farm food waste, which is a significant contributor to food waste in developed countries.

In poorer, developing countries, food wastage is more concentrated toward the production side. Lacking technology and infrastructure for transportation and processing means increased losses to pests, spoilage, and weather. Methods to improve shelf life such as pasteurization and refrigeration are almost always absent in places where food is produced mainly by rural smallholders. Unfortunately, there is much less information about food waste in poor nations than in wealthy countries possibly because it is more difficult to gather information about the former. Food waste in developed countries accounts for the majority of worldwide waste, yet in developing countries it is still a huge problem because poorer regions often feel economic costs such as higher food prices and environmental costs such as water depletion more severely than developed areas do.

The above chart from a 2010 report on food security compares the sources of food waste in developing countries to those in developed countries such as the U.S. and the U.K. Each bar represents the total food waste in a given country, which is divided by color into different categories of food waste. For example food wasted during the “transport and processing” step of the food supply chain is shown in red. The chart shows very clearly that food waste which occurs “on-farm” and during “transport and processing” is the largest contributor in developing countries, whereas in developed countries “home and municipal” food waste dominates.

In an attempt to mitigate these costs which food waste incurs on developing countries, governmental and non-governmental organizations bring improved technology and methodology in food production, storage, transport, and marketing. For example, a recent article in National Geographic explained that “after the FAO gave 18,000 small metal silos to farmers in Afghanistan, loss of cereal grains and grain legumes dropped from 15 to 20 percent to less than 2 percent.” This advancement no doubt improved local livelihoods and contributed to a more secure, steady food supply.

NGOs have also helped to reduce food waste in developed countries like the U.S. These efforts have taken many forms, for example charities that glean unharvested food from farm fields or redistribute unsold food from grocery stores to food shelters. One innovative company called Leanpath produces technology to help retailers monitor their waste, which causes stores to realize the financial cost of wasting food and subsequently leads to decreases in food waste. In the U.K., a huge campaign by the Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) has increased public awareness so that food waste is now a major topic of discussion and thought.

This fall, activist Rob Greenfield rode across the country on his bike and ate only food he found in dumpsters, along the way hosting “Food Waste Fiascos” in which volunteers rescued food from grocery store dumpsters and then gave it away to anyone who needed it. The above photo is from one such gathering in Madison, Wisconsin and shows only a small fraction of the food salvaged from dumpsters there.

Increased public awareness can help begin to shift strongly ingrained habits and mindsets surrounding the value and consumption of food. Even though a simple public awareness campaign might seem like an overused and unhelpful tactic, I think in this case it is a valid approach when implemented in strategic combination with others. Consumers are the greatest contributors to the food waste problem in developed countries, so we are necessarily a huge part of its solution. Simply appreciating all the work and energy that goes into food helps to value it and pay more attention to purchases and habits.

Still, top-down approaches in policy and regulation can also be extremely effective in combating food waste. In 2012 for example, Belgium passed a law requiring supermarkets to donate unsold products to local charities, using these companies’ surpluses to help meet the food needs of the poor. Rob Greenfield points out the many benefits of grocery stores donating food waste: “stores that donate… get tax write offs which means it’s profitable to donate, they spend less on dumpster fees, and most importantly they are doing what is right for their community.” Relaxing laws about cosmetic food standards can reduce on-farm waste of ugly but perfectly edible produce. Tristram Stuart’s idea to remove the ban on feeding food waste to pigs in the European Union would help to cycle the wastes of our food system right back into food production.

Combating food waste is an essential part of meeting the food demands of a growing population: just a 15% reduction in food waste in the U.S. could feed 25 million Americans, according to the same 2009 study cited earlier. Though many stress agricultural intensification and yield increases as the only solution to problems of food security, reducing food waste is clearly also part of the answer. When the problem is that many people don’t have enough food, we can try to grow more food and achieve yield increases of a few percent per year or we can distribute more effectively the nearly 40% of food that is currently being thrown away. It is extremely encouraging that this second option is already being explored and that so many viable solutions to this huge problem have been proposed and implemented. Through a diverse range of policy measures, cultural shifts, and non-profit efforts, we are slowly reducing food waste and its costs to developing and developed countries alike.

Hallie Muller on Farming and the Food System

My name is Simon and I will be guest-blogging on the Farm Together Now website about once a month for the next several months. For my first post, I had the privilege of interviewing Hallie Muller of the amazing Full Belly Farm in Guinda, California. I’d love to talk all about the farm, but I’ll leave that to Hallie. Here’s the interview (with some photos of the farm mixed in):

Simon Willig: First, some background information on your farm: what do you grow/raise? Where is your farm located and what is your piece of land like (soil, history, layout, etc.)?

Hallie Muller: Full Belly Farm is a 450-acre CCOF certified organic diversified fruit, vegetable, grain, nut, and sheep farm. Started in 1984 by Paul Muller and Dru Rivers, Full Belly Farm is now home to three generations of farmers and is owned and operated by Paul, Dru, Judith Redmond, Andrew Brait, and Amon and Jenna Muller, Paul and Dru’s oldest son and daughter-in-law. We are nestled in the Capay Valley in Northern California, a valley known for producing some of the highest quality organic fruits and vegetables in California. Our farmland is a beautifully rich clay loam, perfect for growing year-round. The climate in our region allows us to farm every day of the year – with summertime temperatures reaching well over 100º and winter frosts are never so harsh that we cannot grow brassicas and leafy greens.

SW: What is your philosophy/approach to farming? What experiences/ideas inform this approach?

HM: We have created a farm with a “whole system” approach – every action must be made with purpose, thought, and consideration of the impact it will have on the long term sustainability of our farm. We see our farm as a three legged stool – the legs being ecological, economic, and social sustainability – and each leg is of equal importance. The farm must maintain a levels of ecological sustainability – healthy water systems, healthy soil, and biological diversity is vital to the overall success of our fruits and vegetables. Our farm must also be economically sustainable – and we have worked to create a cash flow that is year round through direct marketing and our Community Supported Agriculture program. Finally, the social responsibility and sustainability of our farm manifests itself in the overall health of our crew.

SW: Who performs the labor on your farm: humans, tractors, horses, etc.? Why?

HM: Labor on our farm is performed mostly by humans – every crop we grow (with the exception of nuts and grains) is hand harvested, washed, and packed. This allows for the highest levels of quality control when it comes to our farm’s products. We do use tractors for discing, cultivating, planting, and tilling our soil. Animals are also an essential component to our farm – our sheep, contained in mobile electric fencing, move from field to field eating crop residue. Chickens are used to control pests in our grapes and apples. Goats take care of blackberry brambles near our creek-beds. Our farm has tried to take on a whole system approach – one that looks at every living being on our farm and asks, “how can this creature be useful to our farm?”

SW: How do you approach pest/disease management on your farm?

HM: As an organic farm, we use an approach to pests and diseases that works well in our organic system. Firstly, crops are rotated from field to field on a seasonal basis, rarely appearing in the same field more than once in a three to five year period. Second, we try to keep on top of diseases and pests so that we are in control before the issues become too much to handle. This means that we have created biological diversity around our fields with hedgerows and native plantings that allow for native insect populations, many of whom combat pests in our fields. We also use organic pesticides and we have a [pest control advisor] who helps to advise our farm. Finally, we plant our crops in small, successive blocks which allows us to maintain a “not all of our eggs in one basket” mentality (crop failure, though a loss for our farm, is not the end of the world). Our diversity is our best management method against pests and disease.

You can see in these pictures some of the diversity that Hallie mentions above. For a complete list of what Full Belly Farm grows as well as detailed information and recipes for each crop, check out their awesome crop timeline.

SW: Now for some broader questions about the food system: what is one big misconception consumers may have about food/farming?

HM: In my personal opinion, the biggest misconception is the real cost of food. American’s spend shockingly little on their food supply – and they expect it to be safe, tasty, and reliable. The price that consumers pay in the average grocery store does not reflect the real cost of producing that food. Organic and small scale farmers are often railed against because their food is “elitist” or too expensive for the common person, when in fact the price that those farmers are asking is the reflection of paying farm workers a fair wage, the true cost of organic seed, the true, non-subsidized cost of farmland and equipment and seeds, etc. The best way to change this misconception is through education – we find that our weekly newsletter that is delivered to each of our CSA customers is a great place for that to happen.

SW: What do you think is one of the biggest changes needed within our current food system?

HM: Continued support of small scale farms, less big ag vs. small ag mentality, and more consumer understanding of farming and food systems. There are so many opportunities for change! The thing that is most frightening for us is the movement towards more government regulation and less understanding of the realities of farm life by those making decisions. The Food Safety and Modernization Act has shaken many small farmers to the core – and continues to be a barrier for entry for new beginning farmers. This needs to change!

SW: How can consumers help to bring about change?

HM: Consumers can continue to vote with their food dollars – supporting small farmers at their local farmers markets, shopping at independent grocery stores, and joining CSA’s are great first steps!

In a beautiful example of what Hallie mentioned earlier, the sheep here are eating the leftovers of a chard crop, helping to make way for a new planting and getting a meal in the process.

Check out the Full Belly Farm website and facebook page for more great info and photos.

Thanks for reading,

Simon

Reading into the Farm Bill

This recent article from the New York Times offers deeper insights into some of the positive benefits of the latest Farm Bill (to read the the HR2642 bill for yourself click here). Collected here are some of the details discovered upon a closer read:

“While traditional commodities subsidies were cut by more than 30 percent to $23 billion over 10 years, funding for fruits and vegetables and organic programs increased by more than 50 percent over the same period, to about $3 billion.

Fruit and vegetable farmers, who have been largely shut out of the crop insurance programs that grain and other farmers have enjoyed for decades, now have far greater access. Other programs for those crops were increased by 55 percent from the 2008 bill, which expired last year, and block grants for their marketing programs grew exponentially.

In addition, money to help growers make the transition from conventional to organic farming rose to $57.5 million from $22 million. Money for oversight of the nation’s organic food program nearly doubled to $75 million over five years.

Programs that help food stamp recipients pay for fruits and vegetables — to get healthy food into neighborhoods that have few grocery stores and to get schools to grow their own food — all received large bumps in the bill.”

Farm Bill Round-Up

Over the last few days, the 2014 Farm Bill has come to some resolution after over 2 years of debates stalled progress. Guided by Reps. Frank Lucas (R-Okla.) and Collin Peterson (D-Minn.) and Sens. Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.) and Thad Cochran (R-Miss.), the bill was passed by a vote of 251 to 166 in the House with the Senate voting next week. The bill comes with a $8.6 Billion proposed cut to the Food Stamps program that will result in about “850,000 households will lose about $90 in monthly benefits under the change” according to an article in the New York Times. They continued to explain: “The bill does provide a $200 million increase in financing to food banks, though many said the money might not be enough to offset the expected surge in demand for food.”

SF Gate reported that “Companies and individuals in agriculture made about $93 million in campaign donations during the 2012 presidential campaign and have given $20 million so far in 2014 congressional races.” According to the Center for Responsive Politics, there were 350 lobbyists registered to work on this bill – making it one of the highest rates of any single bill. Food manufacturers were lobbying hard to repeal on the Country of Origin Labling regulation according to Politco: “Six of the most powerful meat and poultry groups — including the American Meat Institute, National Chicken Council and National Pork Producers Council — wrote to farm bill conferees hours before the final language was released, warning them that they will “actively oppose” final passage of the farm bill if it fails to include a resolution on COOL.”

In terms of agriculture specifically, the biggest development is the end to “direct payment” subsidies and a new formula that will help farmers calculate risk of crop failure and subsidies that will form what the American Soybean Association called a “flexible farm safety net” in their interview with an insurance industry website.